To End All Wars (2001) – From despair and anger to Forgiveness.

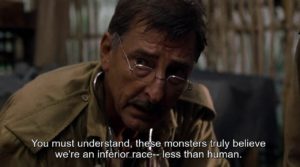

World War 2 usually has a one-sided, one-dimensional portrayal of the Allies. Very rarely are the enemies humanised – even if they are evil. Rarely do the onscreen sufferings translate into a personal, almost spiritual salvation for the person undergoing severe torture and terrible health, yet emerging victorious in spirit at the end of the war. If such a story exists, it will fall into the category of “simply unbelievable.”

To End All Wars answers all the above questions, especially since it’s a true story that leads to a profound, almost spiritual ending.

The Japanese captured Captain Ernst Gordon (Ciaran McMenamin), Major Ian Campbell (Robert Carlyle), and other soldiers from the 93rd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Their tough and caring C.O., Lt.Col. Stuart Mclean (James Cosmo), argues with the Japanese. C.O. about the Geneva convention and is soon shot dead. The Japanese are clear – since the Scottish soldiers have surrendered, they have no honour as they didn’t fight till they died, and thus are no better than enslaved people.

Sergeant Ito (Sakae Kumira), the brutal 2nd in command, is the chief torturer and savagely punishes everyone for minor mistakes and sometimes just for the heck of it. Takashi Nagase (Yugo Saso) is the interpreter who has the thankless job of conveying all the commands to the Allies. There is also an American Lt. Reardon (Kiefer Sutherland) who tries his best to trade with the Japanese.

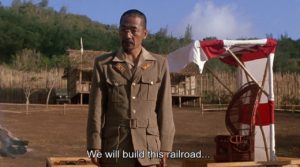

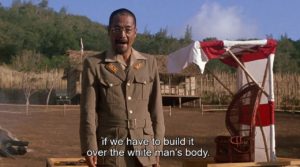

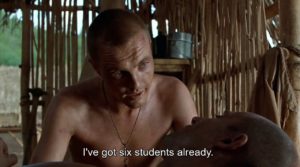

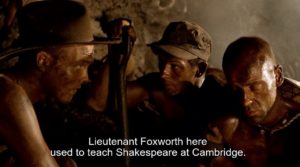

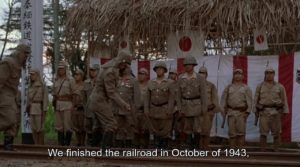

Soon all prisoners, including officers, are ordered to work on the infamous Thailand-Burma “Death” Railway, which should be ready in six months. Gordon soon falls sick and is not expected to survive but is nursed back to health by the camp doctor Coates (John Gregg) and another devout Catholic, Dusty (Mark Strong). Gordon comes up with the idea of a “jungle university”.

He convinces the Japanese to give back the confiscated books in exchange for a promise not to escape, which is frowned upon by Campbell, who takes an aggressive, confrontational approach in all his interactions with the Japanese.

Work on the Death Railway starts, and soon prisoners die in droves. Keeping one’s faith alive in these times while “studying” in the jungle university is also an impossible task.

The onscreen happenings look unbelievable and impossible, but they are all true, as documented in Gordon’s autobiography Through the Valley of Kwai. This only refers to the river Kwai, which flows through Thailand, where the work on the Death Railway began. It has nothing to do with the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai, which could not be more apart in style and is more “glamorous” in showing “British pluck” and “Japanese stupidity”, than the harsh reality of life as a POW.

It all boils down to one thing; most of the time, it is just every man for himself! And Food. Being worked 16 to 18 hours a day and not being fed adequately meant that food became an obsession.

In the 1957 film, building the railway bridge is shown as a matter of British superiority, which was far away from the harsh reality. The real-life POWs built the railway, suffering hundreds of deaths. What is NOT shown in this film – and other POW movies – is that the local civilians, including the Indian population in Malaysia and Singapore, were also forced into working as slave labourers in this project. Here’s a small clip of a Tamil labourer from Malaysia who survived the Death Railway (Unfortunately, no English subtitles)

Another Indian survivor’s story but with English subtitles

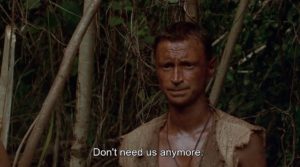

Campbell’s plans to take revenge on Ito, and every Japanese, torture him day and night, especially since everyone knows the war is going badly for the Japanese. Gordon, who has lost his faith, slowly regains it (so much so that after the war, he became a Presbyterian Chaplain). He has enough humanity still left in him to forgive his enemies, unlike Campbell, who is wholly consumed by revenge.

The questions woven into the film are straightforward – can you forgive someone who has physically tortured you and sapped your spirit? Can you forgive your enemies? Broken you as a human? Left you bereft of everything? Can you still stay “sane”? and even earn a “degree”?

The film’s final scene provides the answer as the (real) Gordon and Nagase meet at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery in Thailand.

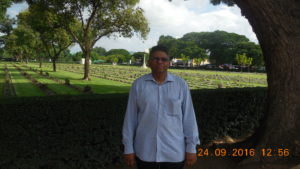

Visiting any war grave is a profound place to ponder the past and perhaps the future. I visited Hellfire Pass (left) and Kanchanaburi War cemetery(right) in 2016; today’s peaceful settings give no clue to the horrific events of those days when the pass was cut using handmade tools. The neatly marked graves are mostly of British, Australian, Dutch and other Allied soldiers whose identities are known. There are none for the civilians. The bridge on the river, which has seen so much suffering, was like a picnic spot with droves of tourists.

This is easily one of the most profound yet moving war films. The war here is within and not outside. That’s where its strength is.

While all the performances are good, Robert Carlyle stands out as the obsessed, possessed Campbell, consumed by revenge. We feel sorrier for him than the others as his purpose is defeated once the Japanese lose the war and Ito commits hara-kiri after being tortured by Campbell.

Mark Strong, always an excellent actor in any role, stands out as Dusty. Unlike Kwai(1957), where all the actors looked healthy, here you can see that some actors are thin and have lost weight. (Most prisoners were only walking skeletons by the war’s end.)

This film is far more believable than the 1957 “Hollywood” production. It also has a profound sense of spirituality – something rare, if not impossible, in a war movie. Hawaii is a good stand-in for Thailand though some scenes were shot in Thailand too.

As for the tile, after WW1 ended, when its cost was calculated, everyone agreed that it had been “the war TO END ALL WARS”. It was felt that such destruction would not happen again, as Humans had learned the cost of WW1, the first “industrialised war” – ‘war to end all wars’. But humans never learn, do we? Perhaps Gordon (and Nagase) has the answer.

Check it out on YouTube https://youtu.be/TD9hsRVteCk

Real History/ Historical background – 4 out of 5

Equipment and Kit – 3 out of 5

Locations or substitutes – 4 out of 5

Script – 5 out of 5

Overall Rating – 4 out of 5

In your upcoming writing, do take up a move “Beyond the enemy lines” I think there is sequel to it as well which I haven’t watched.

Not sure about the content which is real or not but I liked it as it keeps you engaged.

Your thoughts…

Good insights as usual. Thank you Ramesh

Great insights. Thank you Dear Ramesh